This Black Swan Circling for Banks Could Lead to a “Lehman Moment” – Here’s What to Do

Shah Gilani|October 20, 2023

No one’s saying that rising rates will lead to a “Lehman Moment” the way falling home prices sunk subprime bets, obliterated Lehman Brothers, and days later, imploded global banks and economies.

But I’m not no one.

The argument against rapidly rising rates today being anything like the needle that pierced the subprime bubble has it that the web of derivatives dynamite we had back then doesn’t exist today, and therefore won’t get ignited by rapidly rising rates.

And that’s true.

If you recall, back then, artificially lower-for-longer rates forced banks and mortgage lenders to seek product profits by making and packaging subprime loans, which Wall Street turned into mortgage-backed securities (MBS) they exponentially sliced, diced, collateralized, and tranched.

They invented referenced MBS securities (empty pools that merely referenced real mortgages), CDOs and CDO-squareds (collateralized debt obligations with tranches of other CDOs serving as their collateral pool) and, my favorite, CDS, credit default swaps sold as insurance against the Street’s crazy products blowing up.

The insane amount of vertical leverage, of layered derivatives piled higher than the skyscrapers housing the fallen investment banks and too-big-to-fail banks that hid layers of derivative products in off-balance sheet SPVs (Special Purpose Vehicles) and mortgage manufacturing companies that blew up, down to NINJA (no-income, no-job, no-problem home loan applicants) house-flippers, doesn’t exist today.

But what we’re facing now is worse, a lot worse.

Because the bogeyman this time isn’t a layer cake of leveraged bets on a single asset-class, “it’s the economy, stupid.”

It’s basic borrowing, to a feverish degree by consumers and to a bloodcurdling degree by businesses, corporations, and sovereigns.

It’s debt that everyone slathered themselves with when debt service costs were so negligible it paid to borrow more because you could refinance again and again at lower and lower rates thanks to the Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing (QE) money-spraying-spigot running amok for a decade. Then even more money got thrown at us courtesy of central bankers’ bazooka blasts aimed at Covid closures.

And now that rates are sky-high, not long-run historically high mind you, sky-high as in going from 0% to 5.50% in fed funds terms, from 5% to 10 plus-plus% in corporate borrowing terms, from 3% to 8% in 30-year mortgage terms, and from 12% to 29% in credit card interest rate terms, in less than a year and a half. That spike is historical.

That’s why I’ve been saying, in my analyses, in my newsletters, on T.V., “stuff is going to break.”

This time the leverage isn’t piled high vertically, it’s horizontal. It’s spread throughout the economy, from sea to shining sea, and across the globe.

And a lot of it is hidden, which is what’s really frightening this time.

Trillions of dollars of low interest paying loans and low yielding “assets” are held at banks, all banks, everywhere, which most investors know something about. But even more is being held in NBFIs, non-bank financial intermediaries, which almost no one is paying attention to.

What’s terrifying is these proliferating non-bank financial intermediaries aren’t regulated like banks – because they’re not banks. What’s worse, banks lend to them and will be cross-contaminated when they start failing.

And they will fail.

What NBFIs Are and How They Rose to Prominence

Non-bank financial intermediaries range from pension funds and insurers to open-ended mutual funds, money market funds, hedge funds, and increasingly, private credit outfits.

They don’t take deposits from customers, which makes them exempt from requirements for loss-absorbing capital and liquidity buffers imposed on banks. Nor are they subject to any stress tests by regulators to determine how they’d hold up in a range of adverse scenarios.

These nonbank financial institutions are collectively referred to as shadow banks, and they’re huge.

According to the Financial Stability Board (FSB), non-banks had about $239 trillion on their books in 2021. That staggering amount is just under half of the world’s total financial assets. They’ve been expanding their asset base by 7% a year on average since 2008 and leveraging themselves up in the process by borrowing from banks.

NBFIs now manage over 55 percent of U.S. mortgages compared to just 11 percent in 2011 and account for approximately two–thirds of all mortgage originations.

As far as layering, NBFIs, in particular the hot sector these days known as private credit funds, are increasingly lending directly to nonfinancial businesses. At the end of 2021, credit funds had lent out almost $1.2 trillion globally, up from about $600 billion five years earlier.

Nonbank intermediary institutions hold huge amounts of leveraged loans, high interest cost loans typically made to high–risk borrowers already sitting on piles of debt relative to their earnings or net worth. A lot of leveraged loans end up being the financing mechanism used for buyouts, acquisitions, or most commonly, capital distributions, in other words special dividends paid to portfolio company masters.

The huge leverage employed by NBFIs, a lot of it courtesy of big banks that lend to them against their higher-risk loan books as collateral, not only makes these unregulated intermediaries vulnerable to asset quality deterioration. If they stumble, they will almost instantly cross-contaminate the banks they’ve borrowed from.

And those assets are likely to deteriorate.

How Rising Consumer and Corporate Debt Could Bring Us to the Brink of Another Banking Crisis

Consumers and corporations are starting to show cracks, that can turn to fissures of widening delinquencies, then failures in the form of defaults, which will trigger accelerating write-downs, then liquidity lapses, then sales of underwater assets into markets with no bidders, then declarations of bankruptcy, and systemic panic, and eventually the dark shadow of capitulation on an epic scale.

Consumers keep spending, not out of long-ago depleted “stimmy” checks and savings, on their credit cards.

Outstanding credit card debt in the U.S. is now more than $1.03 trillion. Yes, that’s a record. And with rates rising, meaning monthly interest charges of outstanding balances, stuff is starting to break.

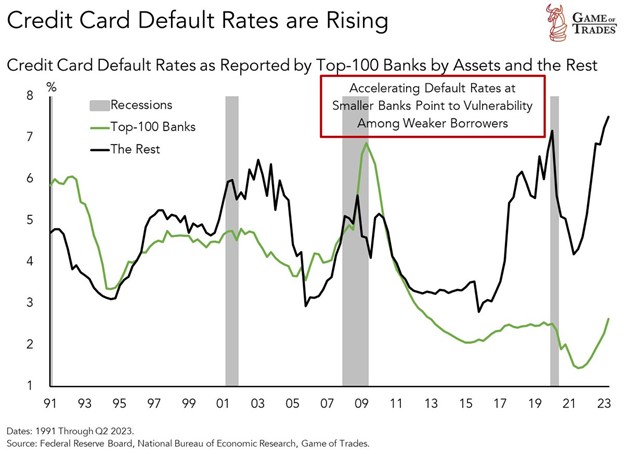

As you can see in the Federal Reserve Board and the National Bureau of Economic Research chart, convened by Game of Trades, credit card defaults at the nations’ top 100 banks are up to 2.45%, while the rest of credit card issuers are seeing defaults spiking to 7.51%, again, the highest level on record.

With 578.35 million credit card accounts capable of taking on $4.6 trillion in available credit limits, balances and delinquencies are likely headed higher along with spiking interest charges. Or as Led Zepplin would put it, “If it keeps on raining the levee’s gonna break.”

That’s just one measure of consumer debt and the stress borrowers are under.

Auto loans outstanding now total more than $1.58 trillion, according to the latest Federal Reserve Bank of New York data. Wells Fargo reported auto loans 30-days delinquent at the end of Q1 2023 rose to 2.3% of loans. Ally Financial’s delinquency rate rose to 3.2%.

Mortgage debt outstanding stands at $12.01 trillion.

All-in the NY Fed’s Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit at the end of Q2 2023 totals $17.06T.

As big as that total is, and as costly as servicing household and consumer debt is becoming, it’s nothing compared to the more immediate refinancing needs of corporations.

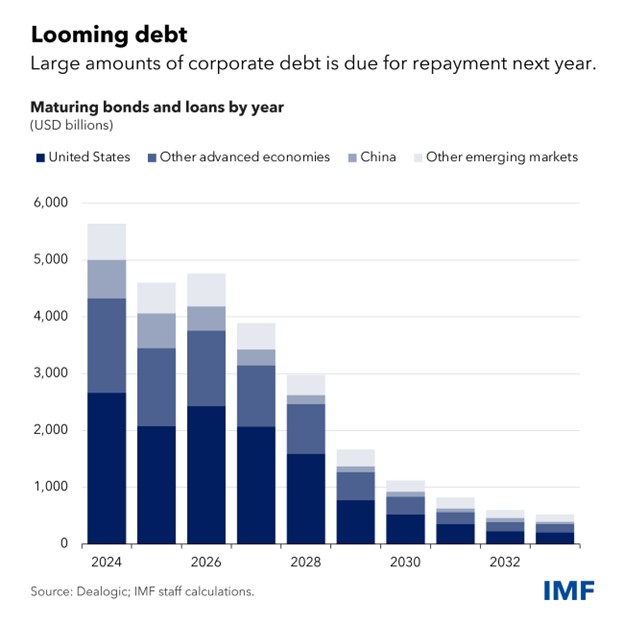

According to Dealogic and IMF staff (see graph below) in the United States alone almost $2.5 trillion of corporate debt will be up for refinancing in 2024.

While the cost of refinancing, with base rates up more than 550 basis points since last March, will stymie many borrowers, an untold number of indebted companies won’t be able to extend and pretend they’re capable of paying back their outstanding debt. They will have to declare bankruptcy. The looming “maturity wall” is a global phenomenon, meaning companies everywhere will face extinction.

It’s already showing up, not just in interest rate spikes, in bankruptcies. Average IG (investment grade) corporate yields are now 6.1% vs 3.38% over the last decade, reflecting how much more interest borrowers are passing through to lenders in the bond market.

Meanwhile, corporate bankruptcies in the U.S. through the end of Q3 2023 are up 40% over 2022, for companies with liabilities greater than $50 mm.

In spite of the higher yields now available to investors, no-one’s loading up. To the contrary, institutional investors fearing rates are headed higher are underweighting allocations to IG and HY bonds this year.

Big firms like Legal & General, with $1.4T AUM, say they are the most underweight investment grade bonds they’ve been in 5 years. Loomis Sayles, with $303B AUM, says their Core Plus Fixed Income portfolio manager, Peter Palfrey, has the biggest underweight in IG bonds relative to the fund’s benchmark since 2008; because Palfrey believes investors are “not being adequately compensated for being in credit.” The firm as a whole is the most underweight in high yield debt they’ve ever been.

Data from the Investment Executive site indicates the quantity of speculative-grade debt (high yield) that’s maturing over the next five years is up 27% from last year’s already-record level, with the amount maturing in the 2024-2025 period up by about 25% to US$333 billion.

With more than US$3 trillion in corporate debt set to mature amid elevated interest rates, “refinancing risks are rising,” says Moody’s Investors Service.

Duh.

On top of all that outstanding consumer and corporate debt sovereigns are indebted to the tune of $92 trillion, not including “off balance sheet” liabilities like America’s Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid plans, or other countries’ unfunded liabilities.

It’s bad enough that debt outstanding is so high, but another paradigm altogether when we consider how much of that outstanding debt was issued over the past 3-15 years yielding low single digits and negative yielding in the case of European sovereign and Japanese issuers, is where it’s sitting and how underwater the holders of trillions of dollars of sovereign issues are.

All the debt, household, corporate, sovereign is held somewhere.

And where matters, because it’s almost all held at banks and non-bank financial intermediaries.

Banks are easy windows to see through. Regulatory requirements mandate reasonable, though far from complete, transparency. Non-bank financial intermediaries, or shadow banks, are black holes for the most part.

For instance, Bloomberg reported about a week before Bank of America’s earnings release this month the giant bank was sitting on $110 billion in unrealized losses in its “held-to-maturity” accounting bucket.

On Friday, October 20, 2023, an analyst on Bloomberg Television said with rates 50 basis points higher than before BAC reported earnings, that loss was more like $139 billion.

Here’s the thing with all those losses, not just sitting on BAC’s books, on every bank’s books, in their held-to-maturity accounting buckets, they’re only losses if they have to sell those “assets.”

Being held-to-maturity means they don’t plan on selling them and will let them mature, whether they’re low yielding Treasuries, corporate bonds, or loans; they don’t have to mark them to market and have those market losses show up in their earnings, because they plan to hold them. That’s a lot of losses for one bank. Imagine how the total pile of underwater assets all banks in the U.S. are sitting on that they don’t plan on selling.

Imagine how big the pile is over on the books, or hidden, at all the non-bank financial intermediaries?

Now imagine if any of them, banks maybe but NBFIs for sure, have to sell underwater assets, because sometimes they have to, regardless of what accounting pile they might have them buried in.

That’ll be a “Lehman Moment” if there are no bidders.

And that’s the problem with NBFIs. And when they fall, they’re going to take a lot of banks with them.

That means you shouldn’t trust banks yet, because they’re not out of the woods by a longshot, and either set yourself up for success by buying in when the stocks crater, or buying puts or put spreads on leveraged loan funds or high yield ETFs like iShares iBoxx $ High Yield Corporate Bond ETF (HYG).

And of course, tune in here for more opportunities as they arise.

Shah Gilani

Shah Gilani is the Chief Investment Strategist of Manward Press. Shah is a sought-after market commentator… a former hedge fund manager… and a veteran of the Chicago Board of Options Exchange. He ran the futures and options division at the largest retail bank in Britain… and called the implosion of U.S. financial markets (AND the mega bull run that followed). Now at the helm of Manward, Shah is focused tightly on one goal: To do his part to make subscribers wealthier, happier and more free.