What I Told Prince Charles About Sustainable Farming

Joel Salatin|November 17, 2020

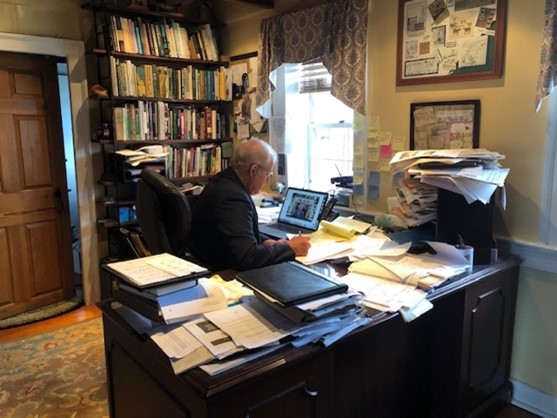

Last week I had the distinct privilege of joining a dozen others for a virtual roundtable with His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, otherwise known as Prince Charles.

He gathered us from several different countries to examine the following question: Why isn’t sustainable farming being adopted more quickly?

Brainstorming With Prince Charles

Brainstorming With Prince Charles

Moderated by Patrick Holden, founder and president of the Sustainable Food Trust in Great Britain, the hourlong session was part of Prince Charles’ Sustainable Markets Initiative (SMI). He has long been an advocate for sustainability across all economic sectors and sees the pandemic as an inflection point to move this agenda forward on a global scale.

Painfully apparent vulnerabilities in our industrial food production and distribution systems have gotten a lot of attention.

The fast-paced roundtable formally examined four hurdles to sustainability. Each participant then had to answer a question on these ideas.

The four themes were finance, labels, certification and smallholder empowerment. Several farmers as well as policy wonks dominated the dozen… but despite their differences, common ideas came to the forefront.

Here are some tidbits for your enjoyment…

The Biggest Hurdles

- Most farmers depend on information from outfits dedicated to making a profit from selling things to farmers. They don’t have the best interests of farmers in mind.

- You can’t have healthy people on an unhealthy planet.

- We need to play to win instead of playing not to lose.

- In the conventional food sector, every retail dollar has another dollar behind it in unseen costs.

- The biggest problem is farm profitability. Margin drives innovation.

- Markets will drive honest pricing if we can create a harmonized definition of “natural capital.”

- The biggest problem is a food system design that assumes cheaper food is somehow better. We need to eat less but better. We need to produce less but better.

- We still don’t have any real benefits from labeling. Labeling as a technique to move consumer choice has limited use.

- If we can agree on 80%, that’s good enough to get going.

- Until we have a harmonized standard of excellence, all we’re doing is confusing farmers and consumers.

- We’re getting close to an empirical measure of nutrient density through a handheld spectrometer. The question is not whether to eat carrots… The question is which carrot is better?

- Smallholders are inherently shut out of the system because any buyer would much rather deal with one large grower than a hundred smaller ones.

- We must remove the myth that small farms are not productive. In fact, the smaller the farm, the more it produces in yield per acre.

- We should measure outputs and not inputs. We should measure nutrition per acre and not production per acre.

- We need diversified market opportunities along with diversified ecologies. Government regulations stifle smallholder access to markets, which diminishes market diversity.

- The three main issues for beginning farmers are startup capital, access to land and regulations that make barriers to market entry for small farmers.

- We need to get rid of the barriers between buyer and seller.

A Measure of Excellence

Now that you have a pretty good taste of the hurdles, here are my comments on the question “What is the opportunity for a universal measure of excellence?”

A new certification program seems to step on the scene every few days, each concentrating on yet another aspect of sustainability, costing the farmer more time and money to comply, and always framed in a pass-fail model.

You’re either in or out.

The result of this is confusion, scale prejudice and lack of comprehensive measures.

What if a metric were established similar to Olympic gymnastics ratings wherein all participants could be placed on a continuum of expertise?

What if we could have a universal language that would comprehensively address all the values of sustainability as a percentage of excellence?

That honors every step toward sustainability and also recognizes different strengths. Very few people are strong on all points. It would allow different players to compensate in their areas of strengths for weaknesses in other areas.

It would let everyone play to their strengths and affirm all steps toward an agreed-upon paradise.

Current certification programs fail to account for significant aspects of sustainability. For example, is soil development more important than the happiness of people working on the farm? Is soil more important than water resiliency? Is any of this more important than business integrity?

A metric capturing these values would put all players on a level field.

Such a metric would honor people rather than confuse them or fail them outright.

As a livestock producer, I’ve brainstormed 10 categories of interest.

- Soil

- Water

- Management (hygiene, comfort, handling)

- Diet (feed type and source)

- Production team (multigenerational, contentment)

- Post-production (slaughtering, packaging)

- Ecological impact (wildlife, pollinators, spiders)

- People interface (community interaction, visitation openness)

- Business integrity (paying bills, honoring agreements)

- Overall beauty

Imagine if each received a point value out of 100 so that a composite could be determined. One outfit would be a 50… another a 70… another an 85.

All attempts toward a utopian sustainability would be rewarded, and all steps backward would be penalized.

As I said, such a system would put all players on a level field… and fairly display strengths and weaknesses.

One final note I’ll mention is that common themes throughout the discussion included both public and private prejudice against smaller farmers getting access to markets. Several folks mentioned government regulations that are “scale prejudicial.”

I’ve voiced these concerns for years, and it was good to see such consensus that freedom to market would encourage sustainable practice.

Now it’s time for these conversations to be had here in the U.S.

Do you think the pandemic will bring about lasting change to food production? Send your thoughts to mailbag@manwardpress.com.

Joel Salatin

Joel Salatin calls himself a Christian libertarian environmentalist capitalist lunatic farmer. Others who like him call him the most famous farmer in the world, the high priest of the pasture, and the most eclectic thinker from Virginia since Thomas Jefferson. Those who don’t like him call him a bioterrorist, Typhoid Mary, a charlatan, and a starvation advocate. With a room full of debate trophies from high school and college days, 12 published books, and a thriving multigenerational family farm, he draws on a lifetime of food, farming and fantasy to entertain and inspire audiences around the world.